A Clinical Audit Report on Compliance to Hepatitis B Vaccination in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in a Primary Health Care Centre in Qatar

ABSTRACT

Objective: Numerous infectious diseases can be prevented in adults through a “lifetime vaccination strategy.” The burden of

hepatitis B disease was found to be greater in diabetic patients. Since 2011, the American Advisory Committee on Immunization

Practices has recommended that diabetic patients be vaccinated against hepatitis B. Patients with diabetes mellitus are at an

increased risk of contracting hepatitis B virus infection and its complications.

Aim: The purpose of this study was to determine compliance with the audit criterion for hepatitis B vaccination among diabetic

patients and to recommend changes in practice to improve hepatitis B vaccination coverage among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients

under the age of 60.

Methodology: A random sample of 50 patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus aged less than 60 years who presented to Umm

Ghuwailina Health Centre (UMG-HC) during the study period will be evaluated for hepatitis B vaccination records during the audit

period, which runs from August 1st to October 31st, 2019.

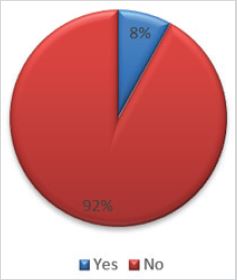

Results: Only 8% (6.8% men and 9.5% women) in the audit group had received hepatitis B vaccine. Hepatitis B vaccination

coverage was found to be low in patients with diabetes mellitus, indicating their vulnerability to this deadly disease.

Conclusion: Hepatitis B vaccination coverage was extremely low among a randomly selected diabetic population in a primary

health care centre in Qatar. This may increase the risk of infection with hepatitis B in this population. In patients with diabetes, the

hepatitis B vaccine is immunogenic and has a similar safety profile to vaccination in healthy controls. Due to the fact that increasing

age is generally associated with a decline in seroprotection rates, the hepatitis B vaccine should be administered as soon as possible

following diabetes diagnosis. Much work is required to raise awareness among health care providers and diabetic patients about the

importance of hepatitis B vaccination.

KEYWORDS

Clinical trial; Infections; DM; Infectious diseases

INTRODUCTION

Infectious viral hepatitis is a significant threat to global health. Hepatitis A and E viruses (HAV and HEV) are endemic in a large number of low-income countries [1]. They typically cause self-limiting hepatitis but can occasionally result in fulminant liver failure and, in extremely rare cases of immunosuppression, chronic HEV infection. Hepatitis B and C viruses both cause acute illness but are more frequently associated with progressive liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and an increased risk of liver cancer (specifically hepatocellular carcinoma) [1]. Hepatitis B infection is a significant global public health problem because it is extremely prevalent throughout much of the world and frequently results in chronic infection, cirrhosis, and liver cancer. Globally, the prevalence of chronic carriage varies between 0.1 and over 20% [2]. Around 15%- 40% of patients with chronic infections will develop liver cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma and 15%-25% will die [2,3]. In 2010, the total annual number of Hepatitis B related deaths was estimated to be around 800,000, placing Hepatitis B as the 15th leading cause of death globally [3,4].

Hepatitis B Virus is primarily spread through percutaneous or mucosal contact with infected blood or other bodily fluids from an infected person. Because Hepatitis B Virus is highly transmissible, approximately one-third of the world’s population has been infected: the majority recover, but many become chronic carriers, primarily depending on their age at infection. Maternofoetal (vertical) and inter-child transmission (horizontal) are the most common routes of exposure, as are drug use, institutionalization, sexual transmission, occupational exposure, blood products and organ transfusions, unsafe injection practices, and cosmetic and cultural practices. As of today (2014), approximately 2 billion people have been infected worldwide, accounting for approximately 30% of the planet’s total population of 7.2 billion [5].

Following an acute infection episode, the likelihood of developing a chronic infection is inversely related to age. Eighty to ninety percent of new-borns and children under the age of one year, as well as 25-30% of children infected between the ages of one and six years, will develop a chronic infection in which Hepatitis B Virus replicates in the liver for the rest of their lives [5]. Adults with a functioning immune system have a roughly 95% chance of eliminating the virus and remaining protected for life in the event of re-exposure [6,7]. The majority of infections in infants and children are asymptomatic, whereas adults have a 30% chance of developing symptomatic acute hepatitis B [7].

The prevalence of chronic Hepatitis B Virus infection varies dramatically across geographies and populations, ranging from 0.1 to 35% at the national level [8]. Hepatitis B Virus endemicity is classified into four (formerly three) levels: low (2%), lower intermediate (2-4.9%), higher intermediate (5-7.9%), and high (8%) endemicity [8]. Males, on average, have a significantly higher prevalence [9].

Around 60% of the world’s population lives in areas with a high prevalence of chronic Hepatitis B Virus [10]. Asia, Sub- Saharan Africa, the Pacific, parts of the Amazon Basin, the Middle East, Central Asian Republics, the Indian subcontinent, and a few countries in Central and Eastern Europe are among the areas where Hepatitis B Virus is highly endemic [11]. In these parts of the world, up to 70%-90% of the population has been infected at some point, and infections frequently occur during childhood, either from an infected mother to her infant (perinatal transmission) or from one child to another (congenital transmission) (horizontal transmission).

The Middle East, Eastern and Southern Europe, South America, and Japan all have intermediate endemic zones for Hepatitis B Virus infection. The infection rate is approximately 10%-60% in these populations, and the chronic carrier rate is approximately 2%-7%. Epidemiologically, infection occurs in both children and adults. Chronic infections are more prevalent in infants as a result of early childhood viral infection exposure [12].

A low prevalence is observed in western and northern Europe, North America, Central America, and the Caribbean, where chronic Hepatitis B Virus infection is uncommon (less than 2%) and primarily acquired during adulthood [13].

Comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus may increase the risk of Hepatitis B Virus infection. In the United States (US), patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) are twice as likely as healthy adults to develop acute hepatitis B virus infections [14]. Additionally, the seroprevalence of antibodies to the Hepatitis B Virus core antigen is 60% higher in patients with diabetes mellitus than in those without diabetes mellitus [15]. Numerous Hepatitis B Virus outbreaks among patients with diabetes mellitus have been reported in the United States and several European countries [16,17]. 25 of the 29 outbreaks reported in long-term care or assisted living facilities in the United States since 1996 involved assisted blood glucose monitoring [15].

At the end of 2011, the US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended hepatitis B vaccination for adults with diabetes aged 19 to 59 years and at the discretion of the treating clinician for diabetic adults aged 60 years [15]. Similar recommendations have been made in other countries, including Canada and the Czech Republic, and have been adopted by Belgium’s Superior Council of Health [18,19]. Seroprotection rates following hepatitis B vaccination appear to be lower in adults with diabetes mellitus (DM) or renal disease [20-22].

Thus, the aim of this study was (i) to access the compliance to hepatitis B vaccination in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Qatar by conducting an audit report on this behalf and (ii) to provide recommendation of getting the Hepatitis B Virus in the diabetic population.

METHODOLOGY

Population

This was a retrospective study where we reviewed the healthcare records of randomly selected 50 patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus aged between 19 and 60 who presented to Umm Ghuwailina Health Centre (UMG-HC) for their Hepatitis B vaccination records. The study occurred between August 1st, 2019, and October 30th, 2019.

Data Collection

Random selection of 50 patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus aged less than 60 years old who presented to UMG-HC during the study period was evaluated for Hepatitis B vaccination records during the audit period, i.e., between August 1st, 2019, and October 31st, 2019. The patients’ health records were evaluated for Hepatitis B vaccination. This audit was undertaken to evaluate compliance with the hepatitis B vaccination protocol for patients with diabetes under age 60 and suggest recommendations to improve the uptake rate of hepatitis B vaccination in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus patients in UMG-HC.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required as per the retrospective aspect of the present study. However, the audit was approved by the Primary Health care Corporation (PHCC) under the reference (HC/CA.20.001).

Management of Type 2 Diabetic Patients in Qatar

The average outpatient visit for an adult patient with diabetes involves numerous interventions and discussions, including management of multiple medications; assessment of control of glycemia, blood pressure, and dyslipidaemia; counselling regarding diet and exercise; screening for diabetes complications; and often assessment and management of other acute and chronic concerns.

Now clinicians have another intervention for many of their adult patients with diabetes: the vaccination series for hepatitis B virus.

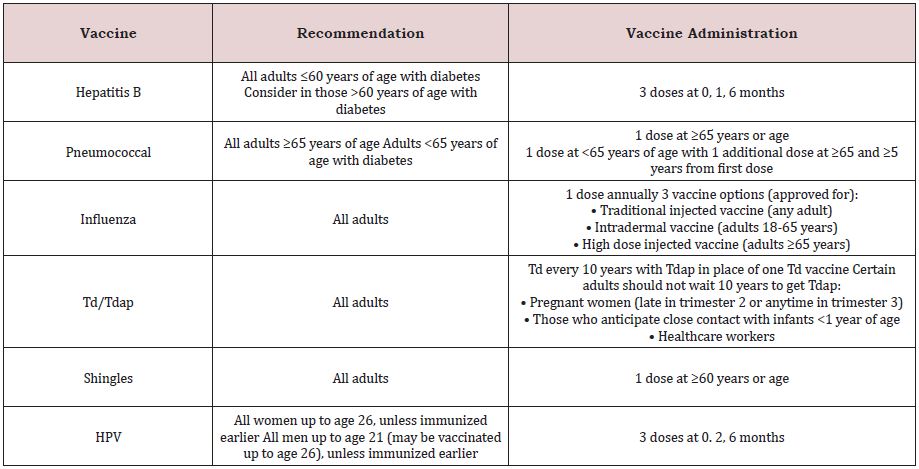

According to the type 2 diabetes vaccination schedule in Qatar and the updated PHCC clinical practice guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes in adults, it is recommended to:

• Provide routine vaccinations for adults with diabetes as for the general population, according to age-related recommendations (Table 1).

• Administer the hepatitis B vaccine to unvaccinated adults with diabetes who are aged 19-59years (for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes CLA-G12V02.0).

RESULTS

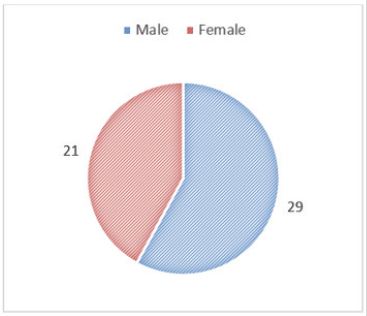

A total of 50 health records of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were reviewed for evidence of hepatitis B vaccination. Key findings showed that the data revealed that amongst the 50 randomly selected patients, 29 (58%) men and 21 (42%) women.

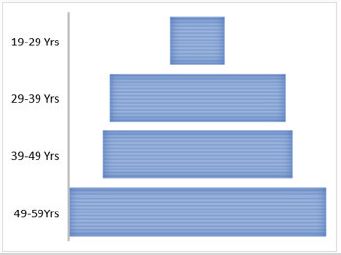

They were between the ages of 19 and 60. Sex distribution is presented in Figure 1 and age distribution is presented in Figure 2.

Amongst all the investigated patients, only 4/50(8%: 6.8% men and 9.5% women) had documented evidence of hepatitis B vaccination in their respective health records (Figure 3).

In 2010, an estimated 18.6 million adults in the United States aged 20 years or older were diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes [25], and the annual incidence of diabetes diagnoses is expected to rise [26]. Diabetes patients require comprehensive medical care to manage their blood glucose levels and avoid complications such as cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, retinopathy, and neuropathy [27]. 86 percent of people with diabetes self-monitor their blood glucose levels at least once a month, regardless of their diabetes treatment (insulin, oral medication, or nutrition) [28,29]. Furthermore, assisted monitoring occurs in a variety of settings, including doctor’s offices, hospitals, health fairs, schools, and assisted-living facilities [30]. Blood-borne pathogens can be transmitted when patients are exposed to infected people’s blood or body fluids via contaminated equipment or surfaces (e.g., on blood glucose monitoring equipment, when insulin pens are used for multiple people, or during certain procedures) [30].

Hepatitis B virus is a highly contagious blood-borne pathogen that is transmitted via percutaneous or mucosal contact with an infected person’s blood or bodily fluids; Hepatitis B Virus is stable on environmental surfaces for 7 days [31]. Injection drug use (IDU), male sex with another male, and sex with multiple partners are all known risk factors for Hepatitis B Virus infection. Unimmunized healthcare workers, as well as household or sexual contacts of a Hepatitis B Virus -infected person, are at a higher risk of infection [32]. Around 5% of otherwise healthy adults infected with Hepatitis B Virus become chronically infected, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver failure [33,34].

Hepatitis B outbreaks among diabetic patients residing in long-term care settings (e.g., nursing homes and assisted-living facilities) suggest that these settings may pose an increased risk of Hepatitis B Virus infection [35]. However, the incidence and magnitude of risk for acute hepatitis B in the general population of adults with diabetes, after excluding individuals whose Hepatitis B Virus infection could reasonably be attributed to other recognized risk behaviors, are unknown.

Adults can currently choose from three Hepatitis B Virus vaccines: Engerix-B (20mg/mL) and Recombivax HB (10mg/ mL) are both single-antigen vaccines that contain only antibodies against the hepatitis B surface. Twinrix (20mg/mL) is another option; it is a combination vaccine that contains antigens for both hepatitis A and B viruses [36].

Numerous studies on the prevalence of hepatitis B have produced inconsistent findings depending on age and region. According to the 2007 report of the hepatitis B consensus meeting, the average rate of HBsAg carriers in the Turkish population is 4-5% [37]. According to the World Health Organization, HBsAg positivity was estimated to be 1-2% in blood donors and 3-4% in the general population in Turkey in 2013, and a total of 1,834,600 people were estimated to be infected with hepatitis B in 2013 [38]. These findings suggest that hepatitis B prevalence has been declining in recent years, with the decline being more pronounced outside of endemic regions. The decrease in the general population can be attributed to a decrease in the prevalence of hepatitis B in children and adolescents following the inclusion of the hepatitis B vaccine in the paediatric immunization program in 1998 [39]. However, because these patients have not reached adulthood, the effects of hepatitis B vaccination on the adult population are not yet evident [40]. Additionally, no study has been conducted on vaccination rates in adults.

Diabetes patients had a higher prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis B-related hospitalizations [41]. Occult hepatitis B was significantly more prevalent in patients with type 2 diabetes than in the control group (11% vs 3%, respectively) [42]. Hepatitis B is a virus that can persist on surfaces for an extended period of time [43]. In institutions, epidemics have been reported as a result of hepatitis B virus transmission via blood glucose monitoring devices and commonly used insulin pens [44]. Additionally, diabetic patients are known to have an increased susceptibility to infections due to abnormalities in their immune systems, which may contribute to their susceptibility to Hepatitis B Virus infections [45]. In patients with poor metabolic control, it is possible to observe impairment of T cell transformation, a decrease in the total number of T cells, and a specific decrease in the CD4 phenotype [46]. Serum immunoglobulin levels are also lower in diabetics than in healthy individuals. In individuals with prolonged type 1 diabetes who have received hepatitis B vaccination, the antibody response to hepatitis B antigens is weak. Impairment in humoral and cellular immune responses can be attributed in part to an inability to recognize antigens [46]. As a result, the immune system abnormalities observed in patients with type 2 diabetes may play a role in the development of hepatitis B.

Prior to the publication of updated vaccination recommendations, surveillance studies revealed that the rate of hepatitis B vaccination was extremely low in diabetic patients. According to data from the United States of America, 19.5 percent of diabetic patients have received a single dose of hepatitis B vaccine, while only 16.6 percent have received all three recommended doses [47]. Another study published in Spain found that 4.2% of diabetic patients received vaccination [48].

The reasons for the low hepatitis B vaccination coverage among diabetics in our study could be attributed to physicians’ fundamental medical knowledge and attitudes; patients’ perceptions and attitudes toward vaccination; low health literacy; financial barriers, systemic limitations; and a lack of vaccine coverage data. Doctor-related barriers to vaccination include a lack of basic knowledge and current recommendations about adult vaccination, inconsistent assessment of vaccination status, and insufficient time spent communicating the benefits of the hepatitis B vaccine [49]. Recommendations that are not supported by public funding mechanisms may result in a decrease in vaccine uptake [50]. Other factors relating to the health care system, such as the absence of reminder-recall systems, immunization records, computerized vaccine registries, and vaccine delivery systems, may contribute to low vaccine coverage rates [51]. A review of the effectiveness of interventions to increase targeted vaccination coverage for influenza, pneumococcal, and hepatitis B vaccines concluded that the only strategy found to be effective when implemented alone was provider reminder systems [52]. Finally, at the national level, a country’s vaccination strategies may be harmed by a lack of surveillance data on vaccination coverage and documented vaccination recommendations [51].

According to the most recent data, the hepatitis B vaccine is cost-effective in diabetic patients aged 20-59 years [53]. Given the economic burden of chronic hepatitis, it would be appropriate to emphasize the importance of preventive measures and widespread hepatitis B vaccination in terms of both individual healthcare and national resources [54].

In conclusion, this preliminary study demonstrated that hepatitis B vaccination status and/or seroprevalence data should be verified at every encounter with diabetic patients in daily practice. Although our study population consisted of a randomly selected adult patient population in a primary health care setting, nearly 8% of patients had a history of hepatitis B vaccination, emphasizing the importance of maintaining a lifelong vaccination log and inquiring about vaccination data.

EXTENSION

In light of the global situation created by the emergence of COVID-19 and the likelihood of severe infection and complications for people living with comorbidities, we recommend tighter control over routine vaccinations such as the Hepatitis B vaccine for all people living with chronic health conditions such as diabetes.

Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a dramatic loss of human life and poses an unprecedented public health challenge [55-70]. COVID-19 has been associated with a variety of complications, particularly in the diabetic population, and it has the potential to be fatal in many cases. Exposure to COVID-19 and hepatitis B may pose a serious threat to the diabetic population.

LIMITATIONS

The primary limitation of this study is the small sample size of 50 patients, which does not represent the entire population of Qatar, even if patient selection was random.

As a result, the findings of this study cannot be extrapolated to the entire Qatari population. Furthermore, this may be an underestimate given the number of patients excluded due to the random selection of patients. Our review of the literature revealed no study from Qatar that quantified the proportion of diabetic patients who are not vaccinated against hepatitis B, implying the need for hepatitis B vaccination. In this regard, we believe that this study provides critical preliminary findings for a country with a high diabetes prevalence.

CONCLUSION

According to the audit, only eight percent of the audit group had received hepatitis B vaccination. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage in patients with diabetes mellitus was found to be low, indicating their vulnerability to this serious and potentially fatal disease. The audit findings demonstrated that significant work remains to be done to raise awareness among health care providers and diabetic patients about the importance of hepatitis B vaccination uptake.

DECLARATIONS

Availability of Data and Material

All data analysed and reported in this study are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Consent to Participate

All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Consent for Publication

All Physicians provided consent for anonymous data use for research purposes and publications. All authors approved of the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for any part of the work.

REFERENCES

- Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C, Vos T, et al. (2016) The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 388(10049): 1081- 1088.

- Lok AS (2002) Chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 346(22): 1682-1683.

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, et al. (2012) Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 380(9859): 2095-2128.

- Ott JJ, Ullrich A, Mascarenhas M, Stevens GA (2011) Global cancer incidence and mortality caused by behavior and infection. Journal of Public Health 33(2): 223-233.

- McMahon BJ (2005) Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis 25(1): 3-8.

- Wright TL (2006) Introduction to chronic hepatitis B infection. Am J Gastroenterol 101: S1-S6.

- McMahon BJ, Alward WL, Hall DB, Heyward WL, Bender TR, et al. (1985) Acute hepatitis B virus infection: relation of age to the clinical expression of disease and subsequent development of the carrier state. Journal of Infectious Diseases 151(4): 599-603.

- Specialist Panel on Chronic Hepatitis B in the Middle East (2012) A review of chronic hepatitis B epidemiology and management issues in selected countries in the Middle East. Journal of Viral Hepatitis 19(1): 9-22.

- Jemal A, Bray F, Centers MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, et al. (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 61(2): 69-90.

- Margolis HS, Alter MJ, Hadler SC (1991) Hepatitis B: Evolving epidemiology and implications for control. Semin Liver Dis 11(2): 84-92.

- Scobie HM, Edelstein M, Nicol E, Morice A, Rahimi N, et al. (2020) Improving the quality and use of immunization and surveillance data: summary report of the working Group of the Strategic Advisory Group of experts on immunization. Vaccine 38(46): 7183-7197.

- Toukan A, Middle East Regional Study Group (1990) Strategy for the control of hepatitis B virus infection in the Middle East and North Africa. Vaccine 8: S117-S121.

- Lok AS, Heathcote EJ, Hoofnagle JH (2001) Management of hepatitis B: 2000-summary of a workshop. Gastroenterology 120(7): 1828-1853.

- Reilly ML, Schillie SF, Smith E, Poissant T, Vonderwahl CW, et al. (2012) Increased risk of acute hepatitis B among adults with diagnosed diabetes mellitus. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 6(4): 858-866.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2011) Use of hepatitis B vaccination for adults with diabetes mellitus: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(50): 1709-1711.

- Thompson ND, Perz JF (2009) Eliminating the blood: Ongoing outbreaks of hepatitis B virus infection and the need for innovative glucose monitoring technologies. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 3(2): 283-288.

- Van Der Meeren O, Peterson JT, Dionne M, Beasley R, Ebeling PR, et al. (2016) Prospective clinical trial of hepatitis B vaccination in adults with and without type-2 diabetes mellitus. Hum Vaccin Immunother 12(8): 2197-2203.

- National Advisory Committee on Immunization (2015) Canadian immunization guide: Part 4-Active vaccines: Rabies vaccine. Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa (ON), Canada.

- Farkas K, Jermendy G (1997) Transmission of hepatitis B infection during home blood glucose monitoring. Diabetic Medicine 14(3): 263.

- Schillie SF, Spradling PR, Murphy TV (2012) Immune response of hepatitis B vaccine among persons with diabetes: a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Care 35(12): 2690-2697.

- Fabrizi F, Dixit V, Martin P, Messa P (2011) Meta‐analysis: The impact of diabetes mellitus on the immunological response to hepatitis B virus vaccine in dialysis patients. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 33(7): 815-821.

- Alavian SM, Tabatabaei SV (2010) The effect of diabetes mellitus on immunological response to hepatitis B virus vaccine in individuals with chronic kidney disease: A meta-analysis of current literature. Vaccine 28(22): 3773-3777.

- Matta TJ, O’Neal KS, Johnson JL, Carter SM, Lamb MM, et al. (2017) Interventions to improve dissemination and implementation of Hepatitis B vaccination in patients with diabetes. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 57(2): 183-187.

- Markowitz LE, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) (2007) Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 56: 1-24.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2011) National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

- Boyle J, Thompson T, Gregg E, Barker LW, David FWD (2010) Projection of the year 2050 burden of diabetes in the us adult population: Dynamic modelling of incidence, mortality and prediabetes prevalence. Population Health Metrics 8: 29.

- American Diabetes Association (2010) Standards of medical care in diabetes- 2010. Diabetes care 33(Suppl 1): S11-S61.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diabetes data and trends (2011) Diabetes data and statistics.

- Burrows NR (2011) National diabetes statistics. In: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), Atlanta, Georgia.

- Klonoff DC (2011) Improving the safety of blood glucose monitoring. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 5(6): 1307-1311.

- Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, Alter MJ, Bell BP, et al. (2006) A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States; recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) part II; Immunization of adults. MMWR Recomm Rep 55(RR-16): 1-33.

- Hyams KC (1995) Risks of chronicity following acute hepatitis B virus infection: A review. Clinical Infectious Diseases 20(4): 992-1000.

- Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, Wang SA, Finelli L, et al. (2008) Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 49(5 Suppl): S35-S44.

- Thompson ND, Barry V, Alelis K, Cui D, Perz JF (2010) Evaluation of the potential for bloodborne pathogen transmission associated with diabetes care practices in nursing homes and assisted living facilities, Pinellas County. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 58(5): 914-918.

- Elgouhari HM, Abu-Rajab TT, Carey WD (2009) Hepatitis B: A strategy for evaluation and management. Cleve Clin J Med 76(1): 19-35.

- Raporu T (2008) Chronic hepatitis B a guideline to diagnosis, approach, management and follow-up 2007 Turkish association for the study of liver. Turk J Gastroenterol 19(4): 207-230.

- Hope VD, Eramova I, Capurro D, Donoghoe MC (2014) Prevalence and estimation of hepatitis B and C infections in the WHO European Region: A review of data focusing on the countries outside the European Union and the European Free Trade Association. Epidemiology & Infection 142(2): 270-286.

- Kanra G, Tezcan S, Badur S (2005) Hepatitis B and measles seroprevalence among Turkish children. Turk J Pediatr 47(2): 105-110.

- Tosun S (2013) Viral hepatitlerin ülkemizdeki değişen epidemiyolojisi. Ankem Derg 27(Suppl 2): 128-134.

- Schillie SF, Xing J, Murphy TV, Hu DJ (2012) Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among persons with diagnosed diabetes mellitus in the United States, 1999-2010. Journal of Viral Hepatitis 19(9): 674-676.

- Demir M, Serin E, Göktürk S, Ozturk NA, Kulaksizoglu S, et al. (2008) The prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 20(7): 668-673.

- Bond W, Favero M, Petersen N, Gravelle C, Ebert J, et al. (1981) Survival of hepatitis B virus after drying and storage for one week. Lancet 1(8219): 550-551.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2011) Use of hepatitis B vaccination for adults with diabetes mellitus: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(50): 1709-1711.

- Marhoffer W, Stein M, Maeser E, Federlin K (1992) Impairment of polymorphonuclear leukocyte function and metabolic control of diabetes. Diabetes Care 15(2): 256-260.

- Holt RI, Cockram C, Flyvbjerg A, Goldstein BJ (2017) Textbook of diabetes. John Wiley & Sons, USA.

- Byrd KK, Lu PJ, Murphy TV (2012) Baseline hepatitis B vaccination coverage among persons with diabetes before implementing a US recommendation for vaccination. Vaccine 30(23): 3376-3382.

- Esparza MN, Hernández BA, Hernández BA, Suria GS, Suria GS, et al. (2013) Serology for hepatitis B and C, HIV and syphilis in the initial evaluation of diabetes patients referred for an external nephrology consultation. Nefrología (English Edition) 33(1): 124-127.

- Hurley LP, Bridges CB, Harpaz R, Allison MA, O’Leary ST, et al. (2014) US physicians’ perspective of adult vaccine delivery. Annals of Internal Medicine 160(3): 161-170.

- Yi S, Nonaka D, Nomoto M, Kobayashi J, Mizoue T (2011) Predictors of the uptake of A (H1N1) influenza vaccine: findings from a population- based longitudinal study in Tokyo. PLoS One 6(4): e18893.

- Kanitz EE, Wu LA, Giambi C, Strikas RA, Levy-Bruhl D, et al. (2012) Variation in adult vaccination policies across Europe: An overview from VENICE network on vaccine recommendations, funding and coverage. Vaccine 30(35): 5222-5228.

- Willis BC, Ndiaye SM, Hopkins DP, Shefer A (2005) Improving influenza, pneumococcal polysaccharide, and hepatitis B vaccination coverage among adults aged <65 years at high risk: A report on recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR Recomm Rep 54(RR-5): 1-11.

- Hoerger TJ, Schillie S, Wittenborn JS, Bradley CL, Zhou F, et al. (2013) Cost-effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination in adults with diagnosed diabetes. Diabetes Care 36(1): 63-69.

- Tosun S, Ayhan MS, İsbir B (2007) Hepatit B Virus İnfeksiyonu İle Savaşımda Ülke Kaynaklarının Ekonomik Kullanımı. Viral Hepatit Dergisi 12: 137-41.

- Varma A, Dergaa I, Mohammed AR, Abubaker M, Al Naama A, et al. (2021) Covid-19 and diabetes in primary care-How do hematological parameters present in this cohort? Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism 16(3): 147-153.

- Musa S, Dergaa I, Abdulmalik MA, Ammar A, Chamari K, et al. (2021) BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy among parents of 4023 young adolescents (12-15 Years) in Qatar. Vaccines 9(9): 981.

- Dergaa I, Abdelrahman H, Varma A, Yousfi N, Souissi A, et al. (2021) COVID-19 vaccination, herd immunity and the transition toward normalcy: Challenges with the upcoming sports event. Annals of Applied Sport Science 9(3).

- Varma A, Dergaa I, Ashkanani M, Musa S, Zidan M (2021) Analysis of Qatar’s successful public health policy in dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Medical Reviews and Case Reports 5(2): 6-11.

- Trabelsi K, Ammar A, Masmoudi L, Boukhris O, Chtourou H, et al. (2021) Sleep quality and physical activity as predictors of mental wellbeing variance in older adults during COVID-19 lockdown: ECLB COVID-19 international online survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(8): 4329.

- Trabelsi K, Ammar A, Masmoudi L, Boukhris O, Chtourou H, et al. (2021) Globally altered sleep patterns and physical activity levels by confinement in 5056 individuals: ECLB COVID-19 international online survey. Biology of Sport 38(4): 495-506.

- Dergaa I, Varma A, Tabben M, Malik RA, Sheik S, et al. (2021) Organising football matches with spectators during the COVID-19 pandemic: What can we learn from the Amir Cup Football Final of Qatar 2020? A call for action. Biology of Sport 38(4): 677-681.

- Mohammed AR (2020) Should all patients having planned procedures or surgeries be tested for COVID-19. American Journal of Surgery and Clinical Case Reports 2(2): 1-3.

- Varma A, Dergaa I, Ashkanani M, Musa S, Zidan M (2021) Analysis of Qatar’s successful public health policy in dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Medical Reviews and Case Reports 5(2): 6-11.

- Varma A, Dergaa I, Zidan M, Chaabane M (2020) Covid-19: “Drive thru swabbing hubs”-safe and effective testing for travellers. The Journal of Medical Research 6(6): 311-312.

- Varma A, Abubaker M, Dergaa I (2020) Extensive saliva based COVID-19 testing- the way forward to curtail the global pandemic. The Journal of Medical Research 6(6): 309-310.

- Musa S, Al Baker W, Al Muraikhi H, Nazareno D, Al Naama A, et al. (2021) Wellness program within primary health care: How to avoid “No Show” to planned appointments?-A patient-centred care perspective. Physical Activity and Health 5(1).

- Dergaa I, Abubaker M, Souissi A, Mohammed AR, Varma A, et al. (2022) Age and clinical signs as predictors of COVID-19 symptoms and cycle threshold value. Libyan Journal of Medicine 17(1): 2010337.

- Varma A, AlDahnaim LA, Al Naama A, Vedasalam S, Mohammed AR, et al. (2021) Screening of asymptomatic passengers’ departure from Qatar: A retrospective observational study. 3(5): 1270-1275.

- Musa S, Dergaa I, Mansy O (2021) The puzzle of Autism in the time of COVID 19 pandemic: “Light it up Blue”. Psychology and Education Journal 58(5): 1861-1873.

- Abdulrahman H, Afify EM, Mohammed AS, Malik RA, Dergaa I (2021) Common Dermatological Complications of COVID 19: How Does it Affect the Skin? OAJBS 3(3): 1034-1038.

- Akbari HA, Pourabbas M, Yoosefi M, Briki W, Attaran S, et al. (2021) How physical activity behavior affected well-being, anxiety and sleep quality during COVID-19 restrictions in Iran. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 25(24): 7847-7857.

Article Type

Research Article

Publication history

Received Date: November 08, 2021

Reviewed: December 05, 2021

Published: December 30, 2021

Address for correspondence

Maxwell Sleiman, Primary Health Care Corporation (PHCC), Doha, P.O. Box 26555, Qatar

Copyright

©2021 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Sleiman M, Sharief M, Waheed MA, Shaik AR, Almajid S. A Clinical Audit Report on Compliance to Hepatitis B Vaccination in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in a Primary Health Care Centre in Qatar. 2021- 3(6) OAJBS.ID.000368

Figure 1: Sex distribution of this investigated population.

Figure 2: Age distribution of this investigated population.

Figure 3: Hepatitis B Vaccine coverage amongst the investigated patients.

Table 1: List of vaccines offered by the Primary Health Care Corporation (PHCC) which is the main governmental Primary Health care facility in Qatar.